Facts you should know about Waitangi Day That the Government will not tell you!

Facts you should know about Waitangi Day

That the Government will not tell you!

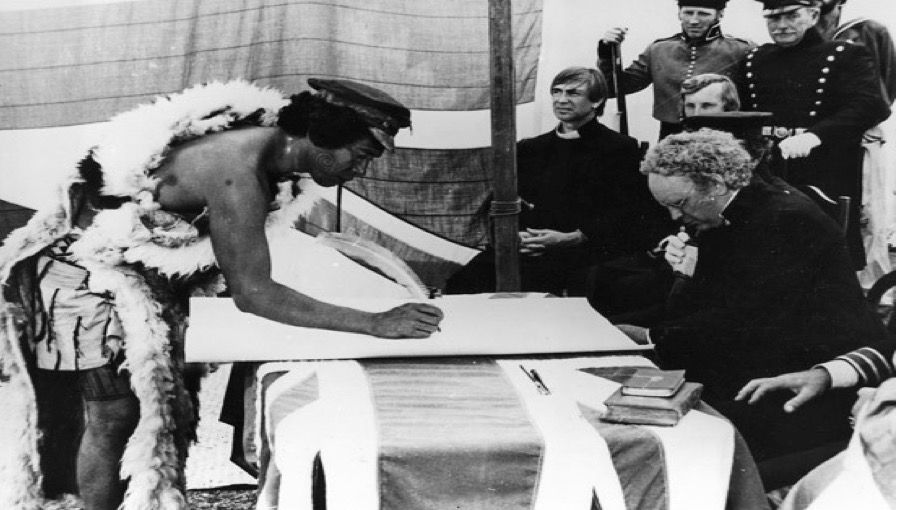

Signing the Tiriti o Waitangi on the 6th February 1840.

Over 500 tangata Maori chiefs signed the Tiriti o Waitangi. This document was the only Treaty signed at Waitangi on the 6th February 1840, “All signatures that are subsequently obtained are merely testimonials of adherence to the terms of that original document”. Lt. Governor Hobson.

“He iwi tahi tatou – We are now one people”

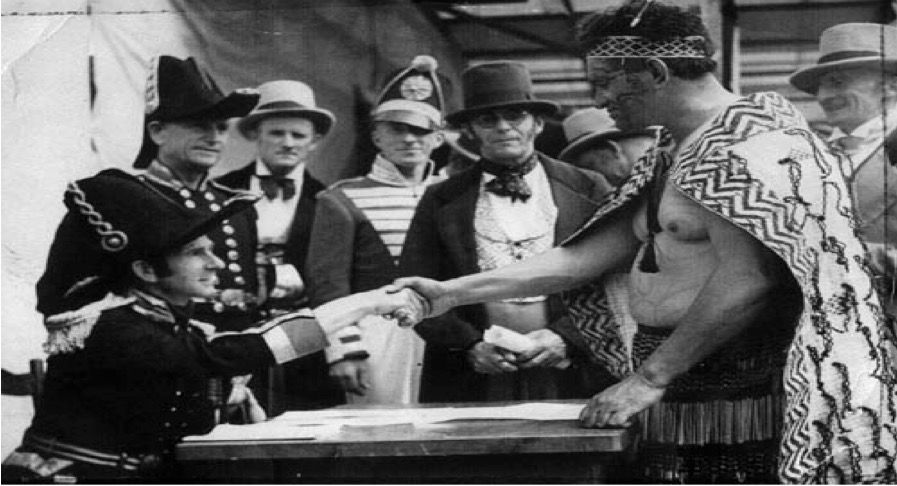

After each tangata Maori chief signed at Waitangi, Lt.Governor Hobson shook their hand with the words, “He iwi tahi tatou – We are now one people”.

“Honour the Treaty but embrace Queen Victoria’s Royal Charter/Letters Patent”

Prepared by the One New Zealand Foundation Inc. www.onenzfoundation.co.nz.

Facts you should know about Waitangi Day

That the Government will not tell you!

The treaty provided nothing more than to save a race of primitive people from extinction.

When did the Canoe People arrive?

Professor Ranginui Walker, past Head of Maori Studies at Auckland University sums up the arrival of the Canoe People on page 18 in the, “1986 New Zealand Year Book”, stating, “The traditions are quite clear on one point, whenever crew disembarked there were already tangata whenua (prior inhabitants). The canoe ancestors of the 14-century merged with these tangata whenua tribes. From this time on the traditions abound with accounts of tribal wars over land and its resources. Warfare was the means by which tribal boundaries were defined and political relations between tribes established. Out of this period emerged 42 tribal groups whose territories became fixed after the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi and the establishment of Pax Britannica”. (Pax Britanica – British Peace).

The Canoe People killed or intermarried with the tangata whenua (prior inhabitants) and continued fighting with each other on a fairly even platform with their primitive hand held weapons until the Europeans arrived with the musket in the 18th Century.

Hongi Hika gains muskets.

When Hongi Hika, Ngapuhi saw the power of the musket, he decided he had to get as many muskets as possible to wage war on his unarmed fellow countrymen. The opportunity arrived for Hongi in 1820 when Rev Thomas Kendall was going to England to help Professor Samuel Lee finish his Maori to English dictionary and needed someone that could speak fluent Maori. Hongi Hika jumped at the opportunity with the ulterior motive of gaining muskets. While the missionaries would not allow him to purchase muskets in England, he did a secret deal with Baron Charles De Thierry for 500 muskets in exchange for 40,000 acres of land in New Zealand. As Hongi was not allowed to buy muskets in England, he had De Thierry ship them to Australia where he picked them up on his way home to New Zealand as well as purchasing more muskets with the gifts the King had given him.

Hongi Hika goes on the rampage south.

When Hongi arrived back in New Zealand with his 500 plus muskets he gathered up 1000 of his tribesmen and went on the rampage south killing, taking as slaves or eating thousands of his unarmed countrymen. It is estimated between 1820 when he arrived back from England and 1830 over a third of the estimated tangata Maori population of 100,000 to 120,000 were killed.

Ngapuhi fear utu.

In 1831, with the Southern tribes now arming themselves with muskets, Ngapuhi could see they were preparing for utu – revenge against Hongi Hika and his people and 13 paramount Ngapuhi chiefs decided to write to the King of England asking him to be their guardian and protector, not only from the French, but also from the Southern tribes.

A British Resident was sent.

As Britain did not want to get involve in New Zealand, James Busby was sent to New Zealand in 1833 to be British Resident to bring peace amongst the people of New Zealand, but without troops, he could do little to relieve the tension. Busby was called, “A man of war without guns”.

Declaration of Independence.

James Busby did write the “Declaration of Independence” in 1835 to recognize the native’s sovereignty over New Zealand and to get the chiefs that signed the declaration to meet annually to make laws for peace between the tribes and to encourage trade with the many ships that were calling into New Zealand to refit and stock up on provisions, but intertribal fighting took precedence over political co-operation, as always and the Declaration was abandoned without one meeting taking place.

The Natives continue to fight.

The natives continued to fight after Busby arrived with Waikato slaughtering one third of Taranaki, one third taken as slaves and the rest fleeing south to Wellington where over 900 commandeered the Rodney and made two voyages to the Chatham Island where they slaughtered the Moriori or “farmed them like swine” into virtual extinction. Te Rauparaha also travelled to the South Island and virtually wiped out the South Island tribes. By 1840 over half the tangata Maori population had been killed by their fellow countrymen, either for utu, the fun of it or the love of human flesh.

Two thirds of New Zealand sold before the Treaty was signed.

By 1840 large areas of land had been sold by the chiefs to people from other lands. After Te Rauparaha had attacked and virtually depopulated the South Island, many of the South Island chiefs travelled to New South Wales where they sold large areas of the South Island. By 1840, over two thirds of New Zealand had either been sold to people from other lands or had contracts to purchase. Over 1000 Deeds of Sale are still held in the New South Wales Supreme Court, although most of these were never challenged when New Zealand became British soil, in most cases it was returned to the chiefs and repurchased by the government many time over.

Why a Treaty?

With over two thirds of New Zealand being sold, the native population heading for extinction and the large number of British Subjects that had arrived in New Zealand and set up farms and businesses with the help of the New Zealand Company, Britain had to take more interest in New Zealand’s affairs. After three years of debate, the British Parliament reluctantly decided the best way to achieve this was by treaty with the natives of New Zealand. Captain William Hobson was sent to New Zealand with a 4000 word document from Lord Normanby instructing him on drafting a Treaty to gain sovereignty over all the Islands of New Zealand, but without force. Captain Hobson was made Lt. Governor of New Zealand under Governor Gipps when he reached Australia on his way to New Zealand.

Drafting the Treaty of Waitangi.

Lt. Governor Hobson arrived in New Zealand on the 29 January 1840 and immediately began drafting the Treaty. A couple of days later he became ill and handed over his draft notes to James Busby to complete. Busby drafted a very formal treaty draft that would not be understood by the chiefs. On the 4th February, Hobson had recovered and with Busby, went ashore to James Clendon, the American Consulate’s house to simplify and finalise the “final English draft”. From Hobson’s and Busby’s notes, they drafted the “final English draft” of the Treaty of Waitangi on paper with a, “1833, W Tucker watermark”, supplied by James Clendon.

Translating the Treaty of Waitangi.

At 4-00 pm on the 4th February, Lt. Governor Hobson went to the Rev Henry William’s house for Rev Williams and his son Edward to translate the “final English draft” into the Tiriti o Waitangi. Rev Williams admitted he and his son, who had been in New Zealand since 1823 made minor changes from the final draft to the Tiriti o Waitangi but it did not change the meaning of the treaty in any way. The changes he made were to clarify which group of people Lt. Governor Hobson was referring to in the Treaty. In the Preamble he changed “all the people of New Zealand” to “chiefs and hapus of New Zealand” and in Article 3 he changed “all the people of New Zealand” to “tangata Maori”. Williams left “all the people of New Zealand” in Article 2 as it related to, “all the people of New Zealand”, irrespective of race, colour or creed, possession of their lands, their settlements and their property.

Tangata Maori.

When Rev Henry Williams and his son translated the Treaty into the native language, they used the term “tangata Maori” as it was known in 1840 through the native’s legends and that some natives were pale skinned with red or fair hair that the natives of New Zealand were not the “tangata whenua” as explained by Professor Ranginui Walking in the opening paragraph above. There is still ongoing debate who the tangata whenua were, but native legend and recent research shows the “original people” were “pale skinned with fair or red hair and blue or green eyes”. See, “Skeletons in the Cupboard”,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uosWPzmMhJc &feature=youtu.be

Reading and discussing the Tiriti o Waitangi.

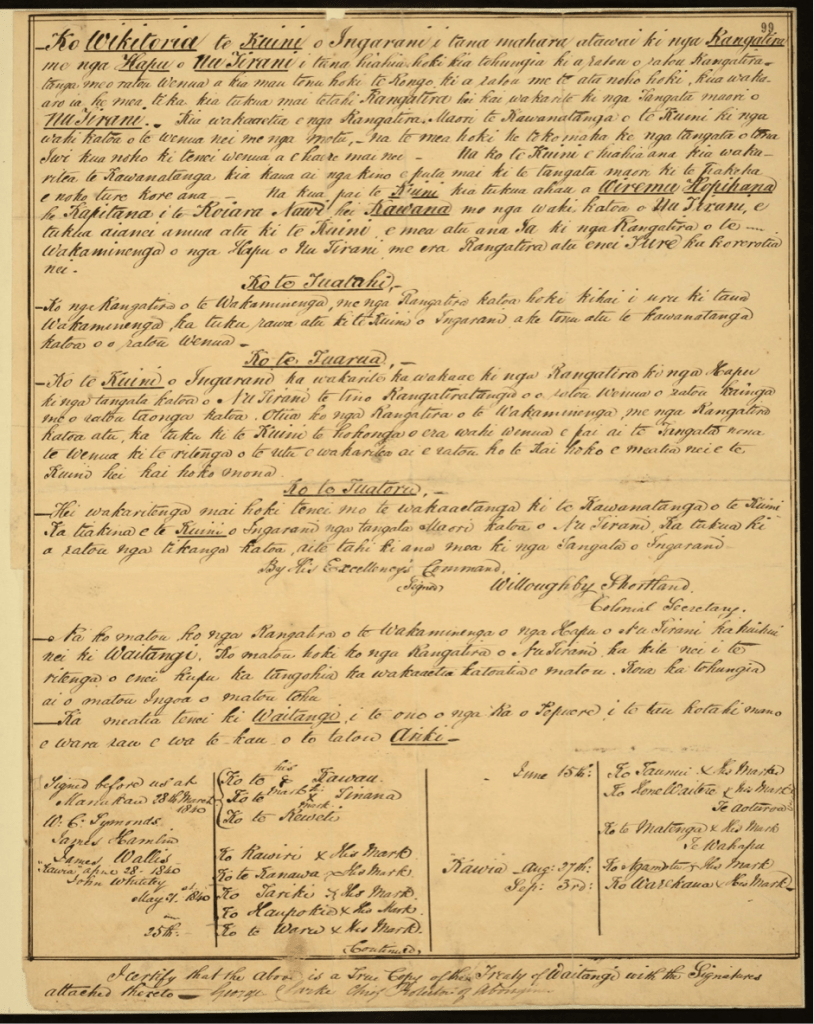

On the 5th of February 1840, Rev Henry Williams read each clause of the Tiriti o Waitangi while Lt. Governor Hobson read the “final English draft” to about 1000 chiefs, their tribes and many Europeans gathered at Waitangi. After the Treaty was read in both languages, there followed a 5 hour discussion on its meaning with some chiefs rejected it while others supported it. At the end of the meeting Hobson told the chiefs he would meet again on the 7 February with those that wanted to sign. All the chiefs then retired to the Te Tii Marae with the missionaries to discuss it well into the night, eventually coming to the decision, it was in their best interest to sign it. As Rev Henry Williams recalls, “We gave them but one version, explaining clause by clause, showing the advantages to them of being taken under the fostering care of the British Crown, by which act they would become one people with the British, in suppression of wars, and every lawless act; under one sovereignty and one law, human and divine.” See certified copy of treaty by George Clarke, Chief Protector of Aborigines, page 11. George Clarke had lived in New Zealand since 1824 and was fluent in the Maori language.

The Tiriti o Waitangi is signed.

As the chiefs had come to the decision to sign the Tiriti o Waitangi on the night of the 5th February, they could not wait until the 7th and summonsed Hobson to sign the Treaty that day, the 6th February 1840. While Hobson was surprised, he came ashore in his casual clothes, except for his “official” hat and proceeded to sign the Tiriti o Waitangi with the chiefs who had gathered with no further discussion or debate. No English version was read, discussed or signed on this day, the 6th February 1840. In 1923, Sir Apirana Ngata, Minister of Native Affairs made this statement in his book, “The Treaty of Waitangi – An Explanation”, “The chief’s placed in the hands of the Queen of England, the Sovereignty and authority to make laws”.

He iwi tahi tatou – We are now one people.

After each chief signed the Tiriti o Waitangi at Waitangi on the 6th February 1840, Lt. Governor Hobson shook their hand and repeated, “He iwi tahi tatou – We are now one people”, to which the whole gathering gave three hearty cheers. The Tiriti o Waitangi gave Great Britain sovereignty over all the Islands of New Zealand and tangata Maori, “the same rights as the people of England”, no more, no less.

Further signatures.

Lt. Governor Hobson then travelled south to gather further signatures but became ill again and had to return to the Bay of Islands. He asked other officials, including the missionaries to continue to gather signatures giving the following instructions. “The treaty which forms the base of all my proceedings was signed at Waitangi on the 6 February 1840, by 52 chiefs, 26 of whom were of the federation, and formed a majority of those who signed the Declaration of Independence. This instrument I consider to be de facto the treaty, and all signatures that are subsequently obtained are merely testimonials of adherence to the terms of that original document”. Over 500 signatures were collected over a 5 month period and Lt. Governor Hobson declared British Sovereignty over all the Island of New Zealand on the 21 May 1840 under the dependency of New South Wales.

The final English draft goes missing.

Soon after Lt. Governor Hobson had read the “final English draft” of the Treaty at Waitangi on the 6th February 1840 it went missing. Therefore, James Freeman, Hobson’s secretary had no English copy to send to Hobson’s superior in New South Wales. Freeman compiled 7 varying “Royal Style” English versions from James Busby’s draft notes to place in his overseas dispatches. Lt. Governor Hobson never authorised or made an English version of the Treaty, stating, “The treaty which forms the base of all my proceedings was signed at Waitangi on the 6 February 1840”. No English version was signed at Waitangi on the 6th February 1840!

There was no “official” English version of the Treaty of Waitangi.

Lt Governor Hobson only made a “final English draft” of the Treaty. He never made or authorized an “official” English version. He had the Church Mission Society print 200 copies of the Tiriti o Waitangi but not one in English. While the Tiriti o Waitangi was “Done” signed on the 6th February 1840 at Waitangi, no English version was “Done” on the 6th February 1840 at Waitangi.

The signed English version.

When Rev Robert Maunsel arrived at Waikato Heads to gather further signatures he was met by over 1500 people. Unfortunately, his “official” copy of the Tiriti o Waitangi had not arrived. Luckily he had one of the CMS printed versions of the Tiriti o Waitangi so he could address the meeting using an “official” printed copy of the Tiriti o Waitangi. This he read to the gathering and discussion followed. When it came time to gather signatures, he used the CMS printed copy but space was limited and only 5 chiefs could sign this copy. He somehow had one of James Freeman’s compiled English versions and used this solely to gather another 39 signatures. When he handed in these two documents for Hobson signature, he had joined the two together with wax. It was also noted he had gathered 44 signatures, 5 on the CMS printed version and 39 on Freeman’s compiled version.

While there is an English version with 39 signatures, including Hobson’s, it was never read or discussed before being signed. It was just a piece of paper that only a few, if any of the chiefs would have understood, attached to the “official” CMS printed version to hold the overflow of signatures when the CMS printed version could hold no more. Hobson did sign this English version, but from the signature, he was a very sick man at the time and it is likely he did not even know what he was signing. He would have seen the attached CMS printed version and thought this was an “official” copy of the Tiriti o Waitangi. It must be remembered it was the only English version with Hobson’s signature on it and from the signature it may not have been his signature!

Queen Victoria or Lt. Governor Hobson did not have the authority to give tangata Maori any special rights or privileges in the Tiriti o Waitangi not enjoyed by all the people of England.

New Zealand Declared British soil and the Treaty is filed away.

Lt. Governor Hobson declared New Zealand British sovereignty under the dependency of New South Wales on the 21 May 1840. The Treaty had served its purpose and was filed away where it should have remained.

New Zealand becomes an Independent British Colony.

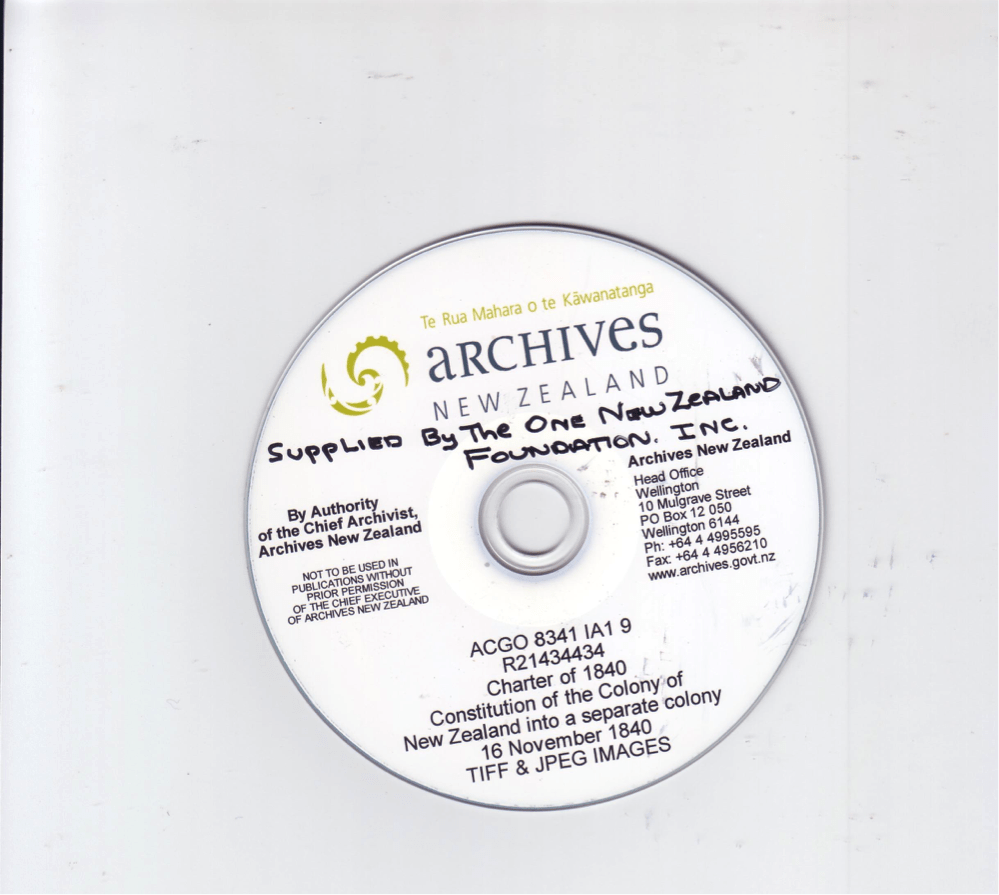

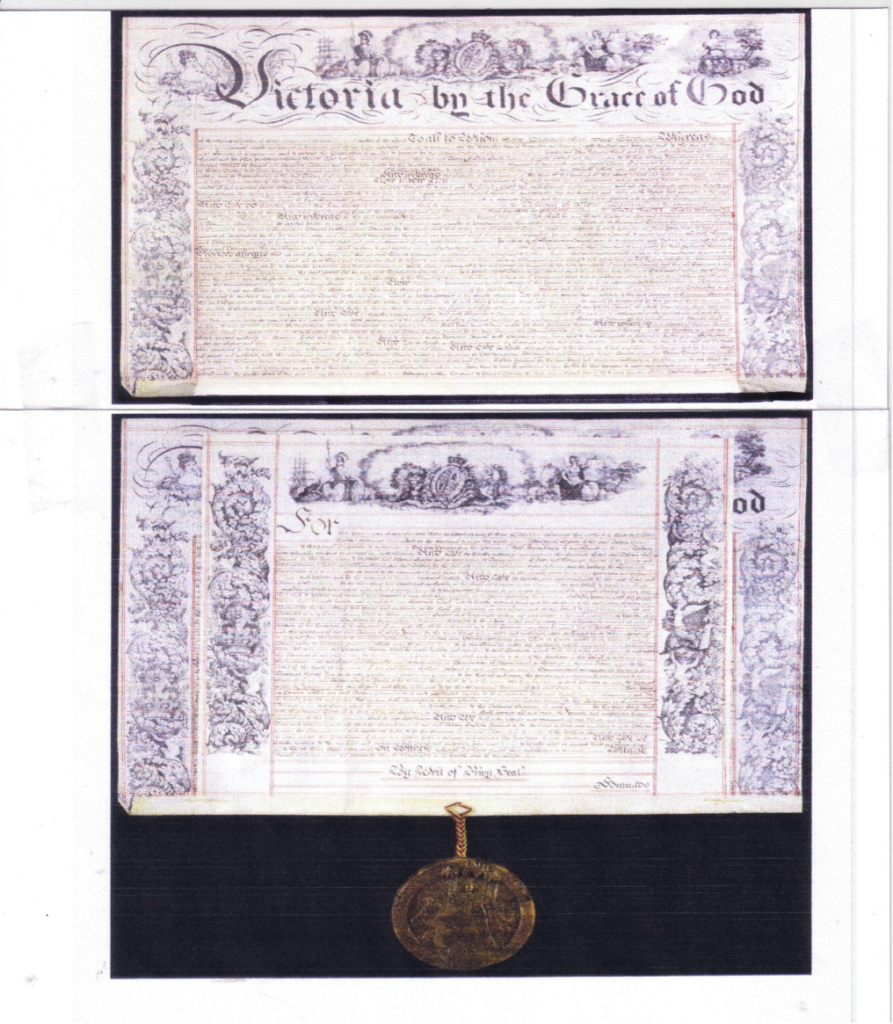

Queen Victoria’s Royal Charter/Letters Patent with its Royal Seal dated the 16 November 1840 separated New Zealand from New South Wales and New Zealand became an Independent British Colony with its own Governor (Governor Hobson) and Constitution to form a legal government to make laws with courts and judges to enforce those laws under one flag and one law, irrespective of race, colour or creed, but under the watchful eye of the British Parliament. The first government was held on the 3 May 1841. Queen Victoria’s Royal Charter/Letters Patent is located in the Constitution Room at Archive New Zealand Wellington. Copy of Queen Victoria’s Royal/Letters Patent Charter page 12.

Queen Victoria’s Royal Charter/Letters Patent completely ignored.

Queen Victoria’s Royal Charter/Letters Patent has been completely ignored by our governments, legislators and historians in favor of the Treaty of Waitangi that only gave Britain sovereignty over all the Island of New Zealand and tangata Maori, “The same rights as the people of England”. No more – no less.

Queen Victoria’s Royal Charter/Letters Patent dated the 16 November 1840 was, “Every New Zealanders true Founding Document and first Constitution, irrespective of race, colour or creed”! It set up our Justice and Political system of one flag and one law for all the people of New Zealand.

186O Kohimarama Conference.

One of the largest gathering of Maori chiefs since the signing of the Tiriti o Waitangi was held at Kohimarama in 1860 where the chief’s swore their allegiance to the Queen’s Rule, with a unanimous vote, “Do not consent that the Treaty should be for the Europeans alone, but let us take it for ourselves. Let this meeting be joined to the Treaty of Waitangi, let us urge upon the Government not to withhold it from us. That this conference takes cognisance of the fact that several chiefs, members thereof, are pledged to each other to do nothing inconsistent with their declared recognition of the Queen’s sovereignty, and of the unions of the two races”.

The First Maori Parliament.

The first Maori Parliament was held in 1879, where once again those gathered swore their allegiance to the Queen’s Rule. While Maori were going to set up their own Parliament, it failed as the Declaration of Independence had failed in 1835. It was obvious the chiefs could not work as a united body for the good of their people.

The Minister of Native Affairs explains the Treaty of Waitangi.

In 1923 Sir Apirana Ngata, Minister of Native Affairs wrote a book explaining the Treaty of Waitangi and the land confiscations entitled, “The Treaty of Waitangi – An Explanation”. This is what he said, “Some have said these confiscations were wrong and that they contravened the Treaty of Waitangi, but the chief’s placed in the hands of the Queen of England, the Sovereignty and authority to make laws. Some sections of the Maori people violated that authority, war arose and blood was spilled. The law came into operation and land was taken in payment. This in itself is Maori custom – revenge – plunder to avenge a wrong. It was their chiefs who ceded that right to the Queen. The confiscations cannot therefore be objected to in the light of the Treaty”.

Full and final Settlements.

Between 1930 and 1940 many of the alleged claims that have been reheard by the Waitangi Tribunal were heard by the Courts and either had “full and final” settlements or were rejected. Many of these settlements were either, full and final payments, paid in perpetuity or paid annually for a specified time.

Statute of Westminster

On the 25 November 1947, New Zealand adopted the Statute of Westminster, passed by the British Government in 1931. The Statute granted complete autonomy to New Zealand in foreign as well as domestic affairs. After 1947, all the people of New Zealand became New Zealand Citizens under one flag and one law, irrespective of race, colour or creed, but since this time, part-Maori, through the 1975 Treaty of Waitangi Act have gained advantages and privileges over their fellow New Zealand Citizens never intended by those that signed the Tiriti o Waitangi in 1840.

1975 Treaty of Waitangi Act.

In 1975 the Government enacted the Treaty of Waitangi Act, which created the Waitangi Tribunal to hear claims by Maori against the Crown after 1975. The Waitangi Tribunal was set up using James Freeman’s compiled English version of the Treaty of Waitangi. While this document has “Done (signed) at Waitangi on the 6th February 1840”, it was never authorized, read, discussed or signed on the 6th February 1840. The English version completely ignored, “All the people of New Zealand” as stated in Article 2 of the Tiriti o Waitangi, therefore giving Maori advantage and privilege over non-Maori never intended by those that signed the Tiriti o Waitangi at Waitangi on the 6th February 1840 with a handshake and the words, “He iwi tahi tatou – We are now one people” or those that signed later.

1985 Treaty of Waitangi Amendment Act.

With many of the 1930/40 “full and final” settlements coming to an end, many tribes tried renegotiating their claims. The Government decided to allow the Tribunal to hear claims dating back to 1840, with many already having “full and final” settlements or rejected as the Te Roroa claim. The Treaty of Waitangi Amendment Act in 1985 now included the Tiriti o Waitangi but the Tribunal had been set up on Freeman’s compiled version, so the “official” Tiriti made little difference to the hearings that are usually held on a Marae under Maori protocol. Maori were still given advantage and preference over all other New Zealanders. Non-Maori are not allowed to lodge claims, participate or appeal the findings or recommendations of the Waitangi Tribunal. While public submissions are called, these are heard by the Maori Affairs Select Committee, therefore most submissions are ignored if not in support of the claim. The 1975 Treaty of Waitangi Act, which set up the Waitangi Tribunal was based solely on one race of people, therefore breached the Tiriti o Waitangi, Queen Victoria’s Royal Charter/Letters Patent, English Law, the Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights Act.

The Tiriti o Waitangi and Queen Victoria’s Royal Charter/Letters Patent gave one law under one flag, irrespective of race, colour or creed.

Five Principles for Crown Action on the Treaty of Waitangi.

Attorney General, Sir Geoffrey Palmer introduced the “Five Principles for Crown Action on the Treaty of Waitangi” in 1986 to make it easier for the Waitangi Tribunal to settle claims. While it appeared in our law, they were not made public until 3 years later. The Principles were based on Freeman’s compiled English version and the Tiriti o Waitangi but the Tiriti had only one Principle, “He iwi tahi tatou – We are now one people”. The Five Principles were to help settle claims between the Crown and Maori without any consideration to non-Maori, except to pay the settlements or give up valuable public assets. The Principles are now part of our law and must be considered by all Government Departments in its legislation. In his book, “New Zealand’s Constitution in Crisis”, Palmer admits, “I thought this a rather elegant legal solution myself”, but he later admitted, “I was wrong”, with his final comment, ““It is true the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975 and all the other statutes, which give explicit recognition to the Treaty are not entrenched. They can be swept away by a simple majority in Parliament,” but he and his fellow politicians have done nothing to correct what Palmer admits, “Was wrong”!

International Law Association, the Hague Conference (2010), Rights of Indigenous Peoples, but Maori are not indigenous!

This conference discussed the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People. While it refers to Maori as the indigenous people of New Zealand, it did not say, “Maori are the indigenous people of New Zealand”. It is up to Maori to prove they are the indigenous people of New Zealand and to date, they have been unable to do so.

This also explains why the Hon Pita Sharples twisted Prime Minister John Key’s arm to allow him to go to the United Nations to sign the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People in 2010, he wanted to make sure Maori jumped on the “band wagon” for more free “handouts” when there is no evidence they are indigenous”.

The Conference went on to say, the Privy Council has ruled that the Treaty of Waitangi is a valid treaty of cession of sovereignty. This recognises that Maori were legally considered capable of holding sovereignty and ceding it to another power. However, under the constitutional system of parliamentary sovereignty adopted in New Zealand, and pursuant to the dualist approach to international law, the Treaty is unable to be enforced directly in New Zealand courts. The only way to enforce any rights accorded under the Treaty are where those rights are enshrined in domestic legislation. Despite the Treaty being unable to be directly enforced without legislative reference, the domestic courts have upheld the Treaty as having an important status as a founding constitutional document.

But the New Zealand Courts have failed to recognise Queen Victoria’s Royal Charter/Letters Patent as our true Founding Document and first Constitution!

The Treaty of Waitangi Act can be swept away by a majority in Parliament

It is also interesting to note, the Hon Sir Geoffrey Palmer, a past Attorney General and Prime Minister and the man that instigated the reforms, stated in his book, “New Zealand’s Constitution in Crisis, “It is true the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975 and all the other statutes, which give explicit recognition to the Treaty are not entrenched. They can be swept away by a simple majority in Parliament”. While Palmer had the opportunity to sweep away 1975 Treaty of Waitangi Act and all the other statutes, he took the easy way out by resigning from Parliament.

The Hague Conference went on to say, in 1975 the Treaty of Waitangi Act was enacted, establishing the Waitangi Tribunal. The Tribunal has exclusive jurisdiction to interpret the Treaty and to determine whether the Crown behaviour complained of is or is not in breach of “the principles of the Treaty”. The Waitangi Tribunal has determined the principles of the Treaty by first looking at the words used in the texts and “the evidence of the surrounding sentiments, including the parties purposes and goals” at the time. It took the approach that: “A Maori approach to the Treaty would imply that its spirit is something more than a literal construction of the actual words used can provide. The spirit of the treaty transcends the sum total of its component written words and puts literal or narrow interpretations out of place”. The Tribunal has accordingly taken a broad approach to both, focusing on the spirit of the Treaty to be derived from the texts and their surrounding circumstances.

The Hague’s main functions is to settle legal disputes submitted to it by sovereign states and to provide advisory opinions on legal questions submitted to it by duly authorized international branches, agencies, and the UN General Assembly but its members agreed with the Waitangi Tribunal taking a broad approach, focusing on the spirit of the Treaty to be derived from the texts and their surrounding circumstances. It seems The Hague is also in fantasy land when it comes to the Treaty of Waitangi!

Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People.

In 2010 Prime Minister the Hon John Key sent the Hon Pita Sharples to the United Nations to sign the, “Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People” without the authority of Parliament or the people of New Zealand. Sharples telling the UN, “Maori hold a distinct and special status as the indigenous people or tangata whenua of New Zealand”, but Professor Ranginui Walker and Maori legion tells a completely different story. The canoe people of the 14 century found tangata whenua (original inhabitants) already living in New Zealand. There is absolutely no forensic evidence that tangata Maori were the Indigenous People of New Zealand but Sharples lied to the UN to “jump on the band wagon – again”!

Maori are no longer a distinct race of people.

“Maori today are a people as one sees in legislation”, Mr. John Clark, past Race Relations Conciliator of Maori descent. Maori are no longer the distinct race of people that signed the Tiriti o Waitangi in 1840. There is too much foreign blood in all Maori today for the Waitangi Tribunal or Government to attempt to compensate one group of New Zealand Citizen at the expense of the others. The degree of intermarriage alone makes it imperative for the Government to come to its senses and call an end to this nonsense. The Government must act in a manner that is consistent with the Treaty of Waitangi, to honour its obligations to “all the people of New Zealand”. Maori have intermarried with people of other races of their own free will until today; they have become a people of many mixed races, far removed from their tangata Maori ancestors. This is confirmed by the need to continually change the legal definition of Maori since the 1865 Native Land Act as their ancestry became further and further diluted with other races.

The Changing Definitions of Maori

With the intermarriage between the races, the Native Land Act of 1865 defined a Maori as, “An aboriginal Native and shall include all half-castes and their descendants by a Native”. As Maori have continued to intermarry with other races of their own free will and their Maori ancestry has become further and further diluted, so has the legal definition of Maori until today they are defined as, “A person of the Maori race of New Zealand and includes any descendant of such a person”. There is too much foreign blood in all Maori today for the Waitangi Tribunal or Government to attempt to compensate this group of New Zealand Citizen at the expense of others. Maori are no longer the distinct race of people that signed the Tiriti o Waitangi in 1840.

The “final English draft” is found.

In 1989, six months after “The Principles for Crown Action on the Treaty of Waitangi” appeared, John and Beryl Littlewood (Needham) were going through their deceased Mother’s estate when they found a document entitled, “The Treaty of Waitangi”. This document, which was named the “Littlewood Treaty” by the Government’s historians, created great excitement amongst the amateur and professional historians, “The “final English draft” of the Tiriti o Waitangi had been found”!

After two years of working on the authenticity of the Littlewood treaty, it was found to be the “final English draft” of the Tiriti o Waitangi, but in 1992 government paid historian, Dr Claudia Orange announced, “It was just another translation of the Maori version by an unknown author“. From its pedigree this could not be so, the fact is, the government did not want the people of New Zealand to know they had made a terrible mistake by using Freeman’s compiled version as the “final English draft” that Rev Williams and his son had translated into the Tiriti o Waitangi or the “official” English version attached to the 1975 Treaty of Waitangi Act. The government therefore, instructed its paid historians and government funded websites to misinform the public that the Littlewood Treaty, “Was just another translation of the Maori version by an unknown author”. The government had used false information to divide the people of New Zealand by stating the Treaty was a “Partnership between Maori and the Crown”. It had also created the Waitangi Tribunal and the “Five Principles” that allowed those that could claim a minute trace of Maori ancestry to receive compensation and valuable assets from their fellow New Zealanders who could not participate or appeal the Tribunal’s recommendations.

On close inspection the document was dated the 4th of February 1840, the day the “final English draft” was written. It was written on paper predating 1840 with an “1833 W Tucker” watermark and it had the word “sovreignty” missing an “e”. Busby had also spelt “sovriegnty” missing an “e” in his draft notes. James Clendon had asked Hobson for a copy of the Tiriti in English to send to his superiors in America and as Henry Littlewood had been Clendon’s solicitor in New Zealand shortly after the Tiriti o Waitangi was signed, therefore it could have quite easily come into his possession and been passed down through the Littlewood family. From its pedigree, this document could only be the “final English draft” Hobson had given to the Rev Henry Williams and his son to translate into the Tiriti o Waitangi at 4-00 pm on the 4th of February 1840 and read to the gathering at Waitangi on the 5th February 1840.

The “final English draft” is virtually word for word to the translation Rev Henry Williams had made, except for the Preamble and Article 3 of the translation having the phase, “people of New Zealand” substituted for “chiefs and hapus” in the Preamble and “tangata Maoris” in Article 3. “All the people of New Zealand” was unchanged in Article 2 as it referred to “all the people of New Zealand”, irrespective of race, colour or creed. No back translation has “people of New Zealand” in the Preamble or Article 3 and all are dated the 6th of February 1840, so it could not be a back translation from the Maori text. “Forests and fisheries” were not mentioned in the “final English draft” or in the Tiriti o Waitangi. It was also confirmed in 2000 by a Government paid historian, it was written by James Busby under Hobson’s instructions.

From extensive research in 1990 and published in the ONZF book, “He iwi tahi tatou – We are now one people” and our continuing research in 2004 and documented by historian Martin Doutré his book, “The Littlewood Treaty – The true English text of the Treaty found”, this could only be the “final English draft”. The English text that the Government has been using was not the document used to translate the Treaty into Maori. Governor Hobson never made or authorised an English version of the Treaty of Waitangi and it would have been impossible to translate the English version attached to the 1975 Treaty of Waitangi Act into the Tiriti o Waitangi. The document found in 1989 by John and Beryl Littlewood (Needham) was the “final English draft” that was given to the Rev Henry Williams and his son Edward at 4-00 pm on the 4th of February 1840 to translate into the Tiriti o Waitangi. It was also the document Governor Hobson had read in conjunction with the Tiriti o Waitangi on the 5 February 1840 and the document he had given to James Clendon to make a copy and sent to his superiors in America and the document that had fallen into the hands of James Clendon’s lawyer, Henry Littlewood that was eventually found in John and Beryl Littlewood’s deceased Mother’s estate in 1989.

Government and the Academics say, “It is not a Treaty”.

After thousands of dollars and many hours of research, the only reason the government and the academics say the “Littlewood Treaty” is not the “final English draft” is because, “it is not signed”, but a draft is never signed! All the evidence confirms the document found by John and Beryl Littlewood in their deceased Mother’s estate in 1989, was the “final English draft” that was translated by the Rev Henry Williams and his son Edward into the Tiriti o Waitangi, which was signed by both parties on the 6th February 1840 at Waitangi with a handshake and the words, “He iwi tahi tatou – We are now one people”, then by over 500 tangata Maori chiefs around the country.

The English version of the Treaty signed at Waikato was never meant to be an “official” English version of the Treaty of Waitangi, it was only used to hold the overflow of signatures at Waikato. Lt. Governor Hobson never made or authorised an “English version” of the Treaty of Waitangi!

The English version of the Treaty of Waitangi was a compiled version by James Freeman, Lt. Governor Hobson’s secretary from James Busby’s early draft notes. It was never read, discussed or signed on the 6th February 1840 as is stated at the bottom of this document. It is a document that has been used by governments over the years in error that has destroyed the honourable intension of those that signed the Tiriti o Waitangi in 1840 to save a race of people determined to become extinct by their own hand. A mixed race of people today that show absolutely no gratitude towards their ancestors, both tangata Maori and European that fought so hard to save them from total extinction!

SUMMARY.

The Tiriti o Waitangi was solely to allow Britain to take control of all the Islands of New Zealand under the dependency of New South Wales by obtaining sovereignty from the tangata Maori chiefs and to give the tangata Maori, “The same rights as the people of England”, Article 3. Article 2 related to “The chiefs, the hapus and all the people of New Zealand possession to their lands, their dwellings and all their property”. Property/taonga has now been distorted to read, “Maori only treasured possessions”!

There was only one “official” Treaty and that was the Tiriti o Waitangi in the Maori language, which was the only Treaty signed on the 6th February 1840. James Freeman’s compiled version was never read, discussed or signed on that day, it was only used to hold the overflow of signatures from the “official” CMS printed Tiriti o Waitangi at Waikato and only had 39 signatures compared with over 500 on the Tiriti o Waitangi. While the Tiriti o Waitangi gave sovereignty to Britain and tangata Maori the same rights as the people of England, it was not New Zealand’s Founding Document!

On the 16th November 1840, Queen Victoria’s Royal Charter/Letters Patent separated New Zealand from New South Wales and New Zealand became a British Colony, with its own Governor and Constitution to form a legal government to make laws with courts and judged to enforce those laws. This document, one of the most important documents in New Zealand’s history is held in the Constitution Room at Archives New Zealand in Wellington. Queen Victoria’s Royal Charter/Letters Patent set up our political and justice system as we know it today, but has been completely ignored by governments in favor of Freeman’s compiled version of the Treaty of Waitangi.

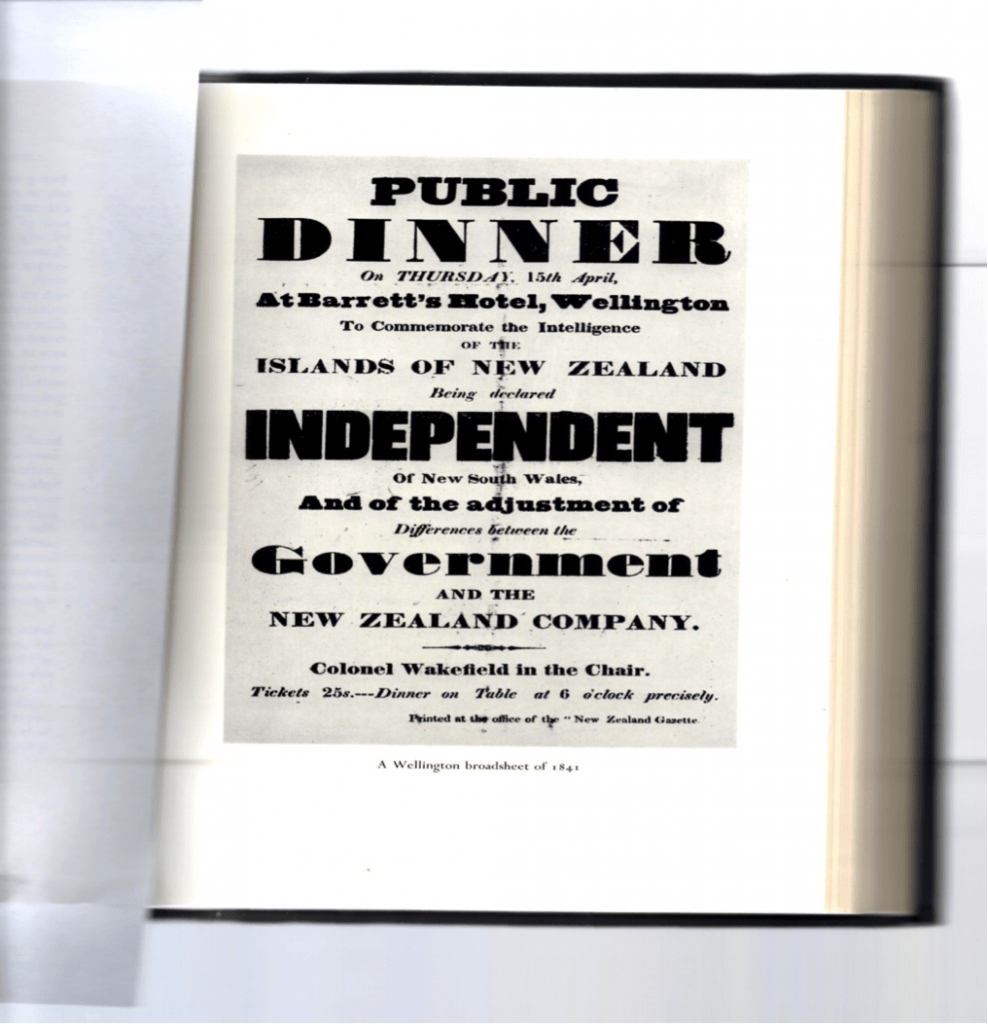

The 3rd of May is the day all New Zealanders must celebrate as their Independence Day, the day New Zealand became an independent British Colony. While the Treaty of Waitangi is important to Maori, it only gave sovereignty to Britain and tangata Maori, “The same rights as the people of England”. Queen Victoria’s Royal Charter/Letters Patent dated the 16th November 1840 made New Zealand into an independent British Colony, which gave, “all the people of New Zealand” one law and one flag, irrespective of race, colour or creed.

While the Treaty of Waitangi (Waitangi Day) is important to Maori as it gave their tangata Maori ancestors, “The same rights as the people of England”, all New Zealander’s must commemorate Queen Victoria’s Royal Charter/Letters Patent as our true Founding Document and first Constitution and May the 3rd as “New Zealand’s Independence Day as the people did in 1841”. Copy of invitation to commemorate New Zealand’s Independence from New South Wales, page 13.

Further information and documented evidence to support the above can be found in the following books published by the One New Zealand Foundation Inc. P.O. Box 7113, Palmerston North. The books are $10-00 each including P & P while stocks last.

Year Name ISBN

1992 He iwi tahi tatou – We are now one people. 0-473-02600-7

1998 From Treaty to Conspiracy – A Theory. 0-473-05066-8

2011 New Zealand in Crisis. 978-0-473-18629-6

2013 Stolen Lands at Maunganui Bluff. 978-0-473-24939-7

2013 Colonisation – The Salvation of the Maori Race. 978-0-473-24938-0

- Queen Victoria’s Royal Charter. 978-0-473-25808-5

Treaty of Waitangi, [New Zealand], 6 February 1840: sheet of the text of the treaty, in Maori, with the names of the signatories. Certified as a true copy by George Clarke, Chief Protector of Aborigines, New Zealand. Copyright: © British National Archives.

George Clarke had lived in New Zealand since 1824 and was fluent in the Maori language. Clarke was also very active in government helping to bring peace between the two races.

Supplied by the One New Zealand Foundation Inc. www.onenzfoundation.co.nz.

Disk supplied by the Authority of the Chief Archivist, Archives New Zealand.

Queen Victoria’s Royal Charter of 1840.

Constitution of the Colony of New Zealand into a separate colony, 16 November 1840.

Queen Victoria’s Royal Charter/Letters Patent dated the 16 November 1840. New Zealand’s true Founding Document and first Constitution that is completely ignored by government in favour of the Treaty of Waitangi. This document separated New Zealand from New South Wales giving New Zealand a Governor and Constitution to form a government to make laws with courts and judges to enforce those laws under one flag and one law, irrespective of race, colour or creed. A far more prestigious document than the Tiriti o Waitangi, which was file away after Lt. Governor Hobson declared sovereignty over all the Islands of New Zealand.

Queen Victoria’s Royal Charter/Letters Patent dated the 16th November 1840.

“Our true Founding Document and first Constitution”.

This is a copy of the public invitation to a dinner to celebrate all the Islands of New Zealand being declared Independent of New South Wales on the 3rd May 1841. This is the day ALL New Zealanders must celebrate as OUR Independence Day. The day all the people living in New Zealand became one people under one flag and one law, irrespective of race, colour or creed.

“He iwi tahi tatou – We are now one people”.

This article was prepared and written by Ross Baker, Researcher, One New Zealand Foundation Inc. 2016. (C)

For further information or to become a member of the ONZF by logging onto, www.onenzfoundation.co.nz .