NO TO TAXPAYER FUNDED “SELF RULE” TO TUHOE

NO TO TAXPAYER FUNDED “SELF RULE” TO TUHOE

Tuhoe Confiscations Inevitable and Justified

Part One.

Due to the isolation of Tuhoe, the “1896 Urewera District Native Act” established some 650,000 acres of their land as a reserve – but never gave them full autonomy. It was no more than a “Maori local government” under the control of the Crown. The Government gained Tuhoe’s recognition of the Queen. All tribal powers had to be within the Law, devolved and approved by the Crown. The Crown intended that in due course it would impose “all the responsibilities, liabilities and privileges” of the other iwi that had signed the Treaty on the Tuhoe people. The Colonial Government would not have had the authority to give Tuhoe full autonomy. Britain would definitely not have given uncivilized natives autonomy to part of a British Colony! This “Maori local government” was revoked a few years later.

The media has published many articles to support the alleged Tuhoe claim with much of it based on selective research by the Waitangi Tribunal, Dr Paul Moon, Bruce Stirling and others. However, most importantly, as with many of these claims, there is another side to this story that must also be told. While Tuhoe did suffer at the hands of the government troops and their Maori supporters, they brought it upon themselves by protecting the “rebels” that had violated both Maori and European. Below is a brief account of why the confiscated lands were “inevitable and justified”, as fully documented in New Zealand’s archives.

The media has published many articles to support the alleged Tuhoe claim with much of it based on selective research by the Waitangi Tribunal, Dr Paul Moon, Bruce Stirling and others. However, most importantly, as with many of these claims, there is another side to this story that must also be told. While Tuhoe did suffer at the hands of the government troops and their Maori supporters, they brought it upon themselves by protecting the “rebels” that had violated both Maori and European. Below is a brief account of why the confiscated lands were “inevitable and justified”, as fully documented in New Zealand’s archives.

Tuhoe did not sign the Treaty largely because they were too isolated for it to be taken to them, read, discussed and given the opportunity to sign. Unlike Ngapuhi and other northern tribes, Tuhoe had very little contact with the Europeans, the missionaries or the British Crown and remained this way for many years after the Treaty was signed, when New Zealand was ceded to Britain, which was recognized and accepted by all the major nations of the world.

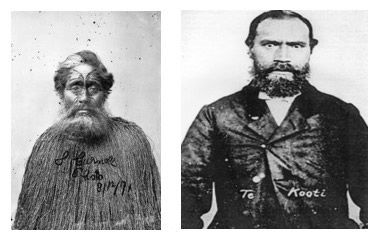

Kereopa Rau Te Kooti

In December 1864, Kereopa brought the Pai Marire religion to the East Coast but was told not to interfere with the Europeans. On the 2 March 1865, missionary Rev C S Volkner was hanged from a willow tree near his church. His body was then decapitated and the head paraded around the village before Kereopa swallowed his eyes, calling one Parliament and the other the Queen and British Law. Kereopa and Mokomoko (whose rope was used to hang Volkner), instigated the killing, as they believed he had been spying for the Government, which caused the death of two members of Kereopa’s family. Although this act outraged the Europeans, such an indignity to the head of an enemy conferred mana amongst Tuhoe. If the government was to honour the commitment Britain had made to all the people of New Zealand in1840, then it was time a stand had to be taken to bring law and order to the people of the East Coast. Although Mokomoko helped instigated the hanging of Rev Volkner and it was his rope that was put around his neck, he claimed he had not taken part in the actual hanging. After he and three other’s trial in Auckland, they were all hanged for Volkner’s killing on the 17 May 1866.

After the killing of Völkner, Kereopa fled to the Urerewas under the protection of Tuhoe. In May 1865, he and a party of Tuhoe attempted to travel to Waikato, but were prevented from reaching the Kaingaroa plains by a force of Te Arawa – but not before killing two Te Arawa chiefs with Kereopa again eating their eyes. They were forced to turn back when a party of Te Arawa, led by W. G. Mair, arrived. Kereopa, under the protection of Tuhoe from the Government troops, returned to hiding in the Ureweras.

Kereopa had much mana in the minds of Tuhoe and thus obtained their continuing protection. The dense bush of the Urewera Mountains offered him protection from the Government troops, as it later would for Te Kooti and the Hauhau. Martial Law had been declared in the Opotiki and Whakatane districts after the killing of Völkner, and a reward was offered for the capture of those responsible.

Over the next three years, the people of the Urewera were weakened, and their land devastated by the government’s relentless pursuit of Kereopa for his involvement with Volkner’s killing; Te Kooti for his massacres up and down the country and the Hauhau who were attacking and killing innocent settlers and their families and destroying their crops and buildings. However, Tuhoe continued to protect these “rebels”. The government troops included Ngati Porou, Ngati Kahungunu and Te Arawa embarked on several campaigns to capture the “rebels”. During these campaigns Tuhoe’s pa were plundered, crops destroyed, people killed and land confiscated. This in itself is Maori custom, – revenge – plunder to avenge a wrong. There is no denying Tuhoe land was devastated, but they brought it upon themselves by protecting the “rebels” from being brought to justice.

By late 1870 several Tuhoe leaders had made their peace with the government, but they would not violate the sanctuary of the Urewera by giving up Kereopa, Te Kooti or the Hauhau. Eventually, however, seeing that their survival was now threatened, they withdrew this protection.

It was agreed amongst Tuhoe that neither European soldiers nor Ngati Porou forces should be allowed to capture the “rebels”: as their protectors, they would deliver Kereopa themselves to the government. Kereopa agreed to give himself up as payment for the Tuhoe blood that had been shed for him.

It must be remembered that it was not only the government that wanted law and order established on the East Coast. Ngati Porou, Ngati Kahungunu and Te Arawa also fought with the Government troops, as did many other tribes around New Zealand to enforce the Queens Law. These three iwi were instrumental in the 1870 and 1871 pursuit of the “rebels” that Tuhoe allowed to take refuge in Urewera Mountains after massacres in Poverty Bay.

There is no denying that Tūhoe, Te Whakatōhea and Ngāti Awa were out of step with the majority of New Zealand, both Maori and European at the time, which they eventually realised, releasing the “rebels” they had been protecting. By this time, the majority of Maori had realised that for the Maori race to survive, there had to be one government, one law for all the people of New Zealand and had put this law in the hands of the Britain Crown.

Due to the isolation of Tuhoe, the “1896 Urewera District Native Act” established some 650,000 acres of their land as a reserve – but never gave them full autonomy. It was no more than a “Maori local government” under the control of the Crown. The Government gained Tuhoe’s recognition of the Queen. All tribal powers had to be within the Law, devolved and approved by the Crown. The Crown intended that in due course it would impose “all the responsibilities, liabilities and privileges” of the other iwi that had signed the Treaty, on the Tuhoe people. The Colonial Government would not have had the authority to give Tuhoe full autonomy. Britain would definitely not have given uncivilized natives autonomy to part of a British Colony! This “Maori local government” was revoked a few years later.

Over the next 60 years, Tuhoe sold large tracts of their underdeveloped wasteland to the Government. Later the Crown vested most of this land into the Urewera National Park for all the people of New Zealand to enjoy, including the people of the Eastern tribes.

The Waitangi Tribunal stated that Tuhoe had 24,147 ha of land confiscated, but Government figures show, in 1866, 448,000 acres (181,000 hectares) of land belonging to the tribes of the Bay of Plenty, Tūhoe, Te Whakatōhea and Ngāti Awa were confiscated by the government. Government documents show, this area was subsequently reduced to 211,000 acres (85,387 hectares), of which Tūhoe lost 14,000 acres (5,700 hectares).

The Waitangi Tribunal also claims Tuhoe were never compensated, but in Richard Hill’s Justice Department report for the Lange Government in 1989, page 11 clause 31, shows Tuhoe received $200,000 compensation in 1958. Tuhoe is also a party to the Waikaremoana Trust Board that receives $124,000 per year in rental for Lake Waikaremoana.

The alliance of the Tuhoe with Kereopa, Te Kooti and the Hauhau and their resistance of the Crown to apprehend these “rebels” after killing many innocent Maori and European – meant military action was inevitable and justified – a fact admitted by the Waitangi Tribunal stating, “The alliance of the Tuhoe people with Te Kooti and the attacks on the Crown’s subjects, Maori and Pakeha that followed, meant military action was inevitable and justified” – as was the confiscations. If New Zealand was to be civilised as the majority of the chiefs had asked for in 1840, then the action taken by the government of the day was inevitable and justified, especially when the compensated land was reduced to only 5,700 ha and Tuhoe received $200,000 compensation in 1958 and the ongoing rental of Lake Waikaremoana– a fact not mentioned by the Waitangi Tribunal.

This “Kangaroo Court” method of determining our countries future by the Waitangi Tribunal and Government must stop. There must be a full public inquire were all the documented evidence is presented and scrutinised before more land and assets belonging to the people of New Zealand are given away without their, knowledge, authority or consent. This is our sovereign right Prime Minister and the people also deserve balanced reporting from our media!

Compiled by the One New Zealand Foundation Inc from files held in New Zealand’s Archives.

© Ross Baker.

Tuhoe – the untold facts.

Part Two.

The Waitangi Tribunal stated that Tuhoe had 24,147 ha of land confiscated, but no mention is made that this was reduced to 5,700 ha with a later compensation payment of $200,000 in 1958.

Government figures show, in 1866, 448,000 acres (181,000 hectares) of land belonging to the rebel tribes of the Bay of Plenty, Tūhoe, Te Whakatōhea and Ngāti Awa were confiscated by the government. Government documents show, this area was subsequently reduced to 211,000 acres (85,387 hectares), of which Tūhoe lost 14,000 acres (5,700 hectares).

The Waitangi Tribunal also claims this land was never compensated for, but in Richard Hill’s, Justice Department report for the Lange Government in 1989, page 11 clause 31, shows Tuhoe received $200,000 compensation in 1958.

From this article by Steven Oliver published in the “Dictionary of New Zealand Biography” there is no doubt the Government of the day had every right to confiscate land from Tuhoe.

Te Rau, Kereopa ? – 1872

Ngati Rangiwewehi warrior, Pai Marire leader

Kereopa Te Rau was one of the five original disciples of Te Ua Haumene, the founder of the Pai Marire faith. He was a member of Ngati Rangiwewehi of Te Arawa. The date and place of his birth are not known, nor the names of his parents. Some time in the 1840s he was baptised by the Catholic missionary Father Euloge Reignier, and took the name Kereopa (Cleophas). He is believed to have served as a policeman in Auckland in the 1850s. In the early 1860s he fought in the King’s forces in Waikato. His wife and two daughters are thought to have been killed at Rangiaowhia, near Te Awamutu, when it was attacked by government forces on 21 February 1864, and the following day he was at Hairini, a defensive position just west of Rangiaowhia, where he saw his sister killed.

After the defeat of the King movement forces in mid 1864, Kereopa joined the new religion of Te Ua Haumene. In December 1864 Te Ua instructed Kereopa and Patara Raukatauri to go as emissaries to the tribes of the East Coast. They were told to preach the Pai Marire faith in the districts they passed through, to go in peace and not to interfere with Pakeha. Kereopa, however, demanded that a European be given up to him at Otipa, a settlement on the lower Rangitaiki River, and that a Catholic priest be handed over at Whakatane. These requests were refused, but at Opotiki the missionary C. S. Völkner was seized and ritually killed on 2 March 1865. Völkner was hanged from a willow tree near his church by members of his own congregation, Te Whakatohea. His body was then decapitated and Kereopa swallowed the eyes, calling one Parliament and the other the Queen and British law. Although this act outraged Europeans, such an indignity to the head of an enemy conferred mana on Kereopa.

Kereopa was widely believed to have instigated the killing of Völkner. Although he had agreed to it, in fact he did not take part in the actual hanging, and cannot be held responsible. The arrival of the Pai Marire party at Opotiki precipitated the tragedy, but there were complex reasons for Völkner’s death. Principal among these was Te Whakatohea’s anger at the missionary for his actions in spying for the government; in returning to Opotiki at that time Völkner had disregarded the explicit warnings of Te Whakatohea. Kereopa himself may also have sought to avenge the deaths of members of his family at Hairini and at Rangiaowhia, a plan of which Völkner had sent to Governor George Grey.

After the killing of Völkner, Kereopa, with his party of Pai Marire followers, went on to Gisborne, and to the Urewera where he preached the Pai Marire faith among Tuhoe. In May 1865 he attempted to travel to Waikato to preach to the Kingite tribes, but was prevented from reaching the Kaingaroa plains by a force of Ngati Manawa and Ngati Rangitihi. According to one account, in the course of this battle, in which Kereopa’s party was supported by Tuhoe, Kereopa swallowed the eyes of three Ngati Manawa warriors who had been killed and decapitated; it was this repetition of his symbolic act at Opotiki which earned him the name Kaiwhatu (the Eye-eater). After a long siege Ngati Manawa and Ngati Rangitihi abandoned their defences at Te Tapiri and Okupu, in the western Urewera, but Kereopa was forced to turn back when a relief party of Te Arawa, led by W. G. Mair, arrived. He then returned to Opotiki but was driven from there by government troops, and fled into the Urewera.

Kereopa had much mana in the eyes of Tuhoe, as the bearer of the Pai Marire faith to that tribe, and thus obtained their protection. The dense bush of the Urewera Mountains also offered him protection from his pursuers, as it later would for Te Kooti. Martial law had been declared in the Opotiki and Whakatane districts after the killing of Völkner, and a reward was offered for the capture of those responsible. Kereopa concealed himself at Te Roau, on a densely wooded hillside, Te Miromiro, at Ohaua-te-rangi, a Ngati Rongo settlement north of Ruatahuna. Te Roau had never been occupied, and commanded an excellent view of anyone approaching. There Kereopa was able to elude his pursuers for the next five years.

From mid 1868 the Ringatu faith of Te Kooti gained popularity amongst Tuhoe, and the influence of Pai Marire correspondingly faded. The reverence in which Tuhoe held Kereopa also diminished, but Tuhoe did not disclose his whereabouts. Over the next three years, however, the people of the Urewera were weakened, and their land devastated, by the government’s relentless pursuit of Te Kooti and the remaining Hauhau leaders. Government troops, including a Ngati Porou contingent led by Rapata Wahawaha, embarked on several campaigns between May 1869 and early 1872, in which Tuhoe pa were plundered, crops destroyed and many people killed.

By late 1870 several Tuhoe leaders had made their peace with the government. But they would not violate the sanctuary of the Urewera by giving up Kereopa. Eventually, however, realising that their survival was threatened by Kereopa, they decided to withdraw their protection.

Tuhoe tradition gives the following account of the capture of Kereopa. It was agreed among Tuhoe that neither European soldiers nor Ngati Porou forces should be allowed to capture the Hauhau leader; as his protectors, they would deliver him themselves to the government, to ensure that their own mana was retained. Thus a Tuhoe party went to Te Roau, in September 1871, and laid their plans before him. Kereopa agreed to give himself as payment for the Tuhoe blood that had been shed for him. When he went to gather his possessions from his sleeping house, however, he attempted to flee. He was chased and captured by a warrior named Te Whiu Maraki, and taken to Ruatahuna. Because he had broken his word, he was handed over as a prisoner to Rapata and Captain Thomas Porter.

On 21 December 1871 Kereopa stood trial at the Supreme Court at Napier for the murder of Völkner. There was no direct proof of his responsibility for the killing, but a European witness, Samuel Levy, testified that he had seen Kereopa among those who escorted Völkner to the willow tree. On the basis of this evidence Kereopa was convicted of murder and sentenced to death. William Colenso appealed unsuccessfully for clemency on the grounds that the crime had already been punished by executions and land confiscation. Mother Mary Aubert, of Father Reignier’s mission at Napier, stayed with Kereopa during his last night. He was hanged on 5 January 1872 at Napier.

STEVEN OLIVER

Clark, P. ‘Hauhau’. Auckland, 1975

Cowan, J. The New Zealand wars. Vol. 2, The Hauhau wars, 1864–72. Wellington, 1923

‘Rev. C. S. Volkner and the Tai Rawhiti expedition, 1864’. Historical Review 7, No 2 (June 1959): 24–36

‘Trial of Kereopa’. Daily Southern Cross. 2 Jan. 1872

‘The trial of Kereopa: horrible disclosures’. Daily Southern Cross. 29 Dec. 1871

HOW TO CITE THIS BIOGRAPHY:

Oliver, Steven. ‘Te Rau, Kereopa ? – 1872’. Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, updated 22 June 2007 URL: http://www.dnzb.govt.nz/

The original version of this biography was published in the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography Volume One (1769-1869), 1990 © Crown Copyright 1990-2009. Published by the Ministry for Culture and Heritage, Wellington, New Zealand. All rights reserved

The alliance of the Te Urewera people with Kereopa, Te Kooti and the attacks on the Crown’s subjects, Maori and Pakeha that followed, meant military action was inevitable and justified – as was the confiscations. If New Zealand was to be civilised as the majority of the chiefs had asked for in 1840, then the action taken by the Government of the day were “inevitable and justified”, especially when the compensated land was reduced to only 5,700 ha and Tuhoe received $200,000 compensation in 1958 – a fact not mentioned by the Waitangi Tribunal.

Compiled by the One New Zealand Foundation Inc from files held in New Zealand’s Archives.

© Ross Baker.